On my earlier days as a watch collector I often stayed perplexed with the varying luster of the watch material, which was essentially steel. My idea was luster improves with the price, yet found most didn’t glitter the way I would like them to. I am not ashamed to admit that those were the times when numbers and pseudo-oomph counted. Someone in college, yet with one watch for every day of the week (and a separate one for the weekends) was an enviable character. So I was more inclined on taking the number up than brood over the built.

Only when the shiny coatings started peeling off from the bands and cases after a year or two I turned to finding out those that stay. Internet was not as readily available those days (late ‘90s). I finally managed to get some lowdown on stainless steel from one gentleman at an auction house. He was eyeing a tea-table and it never struck me he would know that much on watches. It also didn’t strike that he works for one of the large steel companies. And I admit he knows his business. What I give here are the primary points on detecting the steel that goes into the watch bracelets and cases.

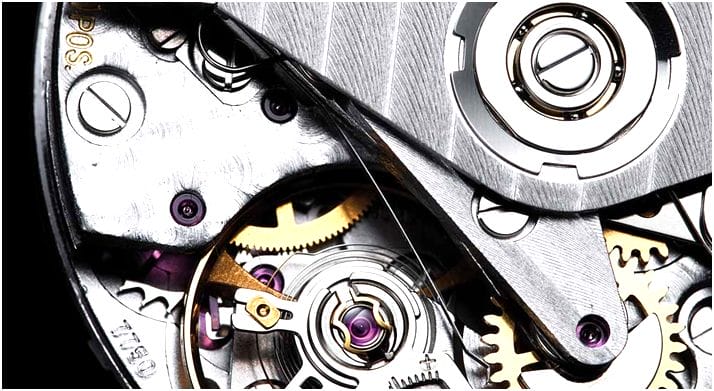

The steel that’s mostly used to make them are 316L, 904L or Surgical Grade Stainless Steel. Now, you must know what stainless steel means exactly. It is not an individual metal/metallic alloy but a generic name for corrosion-resistant steels. This family of steels has several advantages over plain, standard/mild carbon steel. Their corrosion resistance, cryogenic toughness, work-hardening rate, hot strength, hardness and overall strength are much higher; they look better and low to maintain. It’s around 10.5% extra Chromium that brings the difference. The Chromium forms a transparent, protective oxide layer on the steel, which remains intact no matter what fabrication method you use. It is also self-healing by nature, so corrosion cannot bite in. For normal carbon steels, either you need to paint or galvanize. If it goes off, the underlying steel catches rust. It depends on the different grades how bad it will be; also on the environment.

As for stainless steels, they contain anything from chlorides (for medium resistances) to chromium (scratch and corrosion resistance), molybdenum (imparts greater hardness; maintains a cutting-edge) and nickel (for a smooth and polished finish). For example, the 316 Grade denotes molybdenum, which is a step higher than Grade 304 carbon-bearing steels in terms of corrosion resistance. They hold better in chloride environments and are excellent to give shape. They don’t also need post-weld annealing, even for thin sections. The Grade 316L is a low-carbon 316 version while for higher carbon content, it is Grade 316H. If you are worried on whether they make any big difference to watch prices, they do not. But mostly it’s 316L that makes into the watches and they hold extremely well to adverse conditions. Not in sulfuric acid or sodium hydroxide, though. You need 904L for that. Rolex uses 904L but we will keep that for another day.